Sheriffs hold a unique place in American history and politics. As elected law enforcement officers, they arguably wield more power and have less oversight than police chiefs or other appointed officers. In historical accounts of the American West, they have been both celebrated and vilified. And while today the office has become more institutionalized, the figure of the sheriff still looms large in the story of American politics.

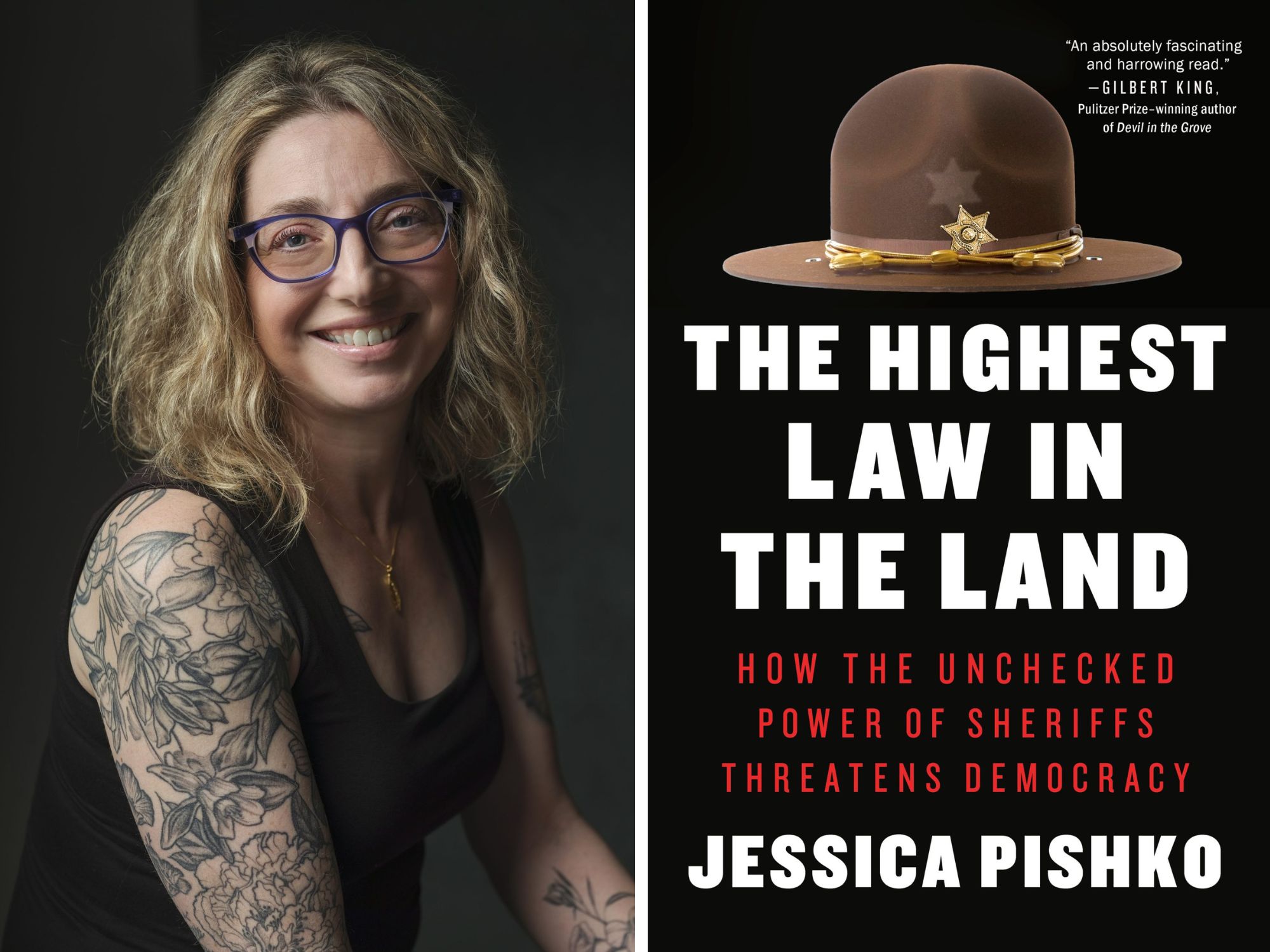

The constitutional sheriff movement claims that the county sheriff has “the ability to determine which laws are constitutional” — as Jessica Pishko lays out in her new book, “The Highest Law in the Land: How the Unchecked Power of Sheriffs Threatens Democracy.”

According to this political philosophy, Pishko writes, sheriffs can “block all other government branches and officials,” Pishko writes, … “from enforcing laws and regulations within their county that might conflict with their specific, originalist interpretation of the Constitution.”

Arizona sheriffs in particular, Pishko argues, have significantly influenced how the nation sees and accepts the role of the sheriff. With local sheriffs poised to play a key role in the incoming Trump administration, Arizona Luminaria spoke with Pishko about the history of sheriffs in Arizona, who oversees sheriffs’ departments, and why jails continue to be so deadly.

The following conversation with Pishko has been edited for length and clarity.

Question: Tell me about your title. Can you lay out why the subtitle, about sheriffs’ power potentially threatening democracy, isn’t alarmist?

Jessica Pishko: The first way in which I meant the title was literally, because of sheriffs’ involvement in the Stop the Steal campaign, because of their distrust in election processes and their desire to quote-unquote, investigate voter fraud. The second way in which I meant the title was actually in a way that’s a little more subtle. One of the things that I think is important to consider when we think about sheriffs is that, because they are elected on a countywide basis, many sheriffs do not represent a substantial number of people. Rather, they represent land.

As an example, North Carolina has 100 counties. So we have 100 sheriffs, but only about five counties contain something like 2/3 of the total state population. When the state sheriff’s association, as they recently did, wanted to press for legislation that would require sheriffs to cooperate with ICE (U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement), they can present 90-something sheriffs who all agree, which looks like a lot of support. But behind that is the fact that those sheriffs do not represent anywhere near half the people living in the state. So, kind of like the Electoral College, you have this situation where rural and suburban areas are able to dictate policing and immigration policy in a disproportionate way. And that burden falls on immigrant communities, people of color, urban areas, all places where people are overly policed.

Q. Let’s move out west. In this book you spend a lot of time in Arizona. How important is the state to the development of the modern-day sheriff?

A. Because it is a growing state and because that population is very heavily Latino in many places, the state sits at this really important nexus of being on the U.S.-México border, having a lot of rural and federal land and also being a place where there’s a great deal of business development and demographic change.

That’s added up to sheriffs exerting a rather large amount of power. I think there’s something to be said for the fact that Arizona is where the far-right sheriffs movement has gotten a lot of traction. It is, of course, the home place of Richard Mack (who founded the constitutional sheriffs movement and was sheriff of Graham County from 1988 to 1996), but it is also the birthplace of Joe Arpaio, and the constitutional sheriff movement owes a lot to Joe Arpaio in many ways.

Arizona’s criminal and prison systems were set up to be tough and cheap, as they say, in terms of policing and punishment. And so the state has long relied on Old West-style, unregulated policing, or, at least, policing that is a little less regulated than many urban police departments. Sheriffs in Arizona have a slightly different style that I argue is more influenced by militias and military service.

Q. What do you mean by “tough and cheap”?

A. I borrowed that from Mona Lynch’s book, what she describes as “a tough and cheap” model of law enforcement that frames violence as a cost-cutting measure. Arizona hired a sheriff (Pima County Sheriff Frank Eyman) to run the first state prison in Arizona, and he ran in with a bunch of his guys and subdued a prison riot. He used tear gas and lined up the leaders of the prison uprising against the wall. Authorities were so pleased with his work that they asked Eyman to run Arizona’s prisons for two decades. During that time, he instituted a “codebook” of military-style rules while ensuring that incarcerated people were forced to work so that the prison could be self-sustaining and, as a result, cost-effective and “efficient.”

Q. But does that differ from how other states rely on sheriffs?

A. I don’t want to suggest other states aren’t tough and cheap because, for example, Texas is a place where tough and cheap also sells well. Arizona has larger and fewer counties, especially compared to eastern states, so originally sheriffs there were set up to police larger territories.

But the idea and modeling in Arizona was that if you use a lot of violence that would subdue populations, you would deter and incapacitate people who might commit crimes. But also there was a policy of not wanting to spend a lot of money on what you might call a rehabilitative model.

Arizona has long had the strategy that, well, we’re not very concerned about rehabilitation, what we’re very concerned about is warehousing people very cheaply, being kind of mean and tough and that sort of translates into things like Joe Arpaio. His style was tough and cheap. The model says, well, I’ll be excessively cruel and violent and not concerned about rehabilitating and programming.

Q. Tell us about Eyman. Not many people have heard of him. Why is he important in this story?

A. Frank Eyman was a very interesting figure because he was a sheriff who was put in charge of the first state prison in Arizona, which was in Florence, and he was there for a very long time, at least 20 years. His claim to fame was that he was a tough-talking sheriff. He was foul-mouthed, and not very polite, and his tactics were incredibly violent. He brought his guys into the prison and would subdue people housed there with pure violence.

His main tactic was just to beat people into submission. He was the first person brought in specifically to tame what was seen as an incredibly unruly population of people housed in Florence.

I think that another trope is that Arizona sheriffs, as with a lot of the West, believed that strict policing was necessary because you had to subdue unruly elements, people who were seen as having been hardened by the environment, hardened by the desert. You can see the same tropes today, especially in immigration policing, this stereotype that immigrants are bad and tough, or the cartels or coyotes are these hardened criminals.

Q. Do you see a partisan divide in how sheriffs run their departments or their jails?

A. The partisan divide among sheriffs is stronger than it used to be although it is also less indicative of outcomes as people might like to assume. It didn’t used to be that the local party dictated your policy. There wasn’t what political scientists would call the realignment of the parties on a local level. But we have seen, since 2016 – and it really is attributable to the rise of Donald Trump – that rather suddenly local politics began to align with national party politics. So you now have sheriffs running as Republicans who support Trump, and sheriffs running as Democrats who do not support him.

But, at the same time, it is not clear that these partisan divides produce different results. For example, sheriffs who run as Democrats believe in ostensible liberal values in policing, like diversity training, de-escalation, programming, and all these sorts of things. It turns out, however, that they do not run safer jails. Overall, jail deaths continue to go up.

Q. Who oversees the sheriff? Or who should? I know some states have oversight of jails, though Arizona isn’t one of them.

A. If I had to pinpoint the greatest harm of the constitutional sheriff movement it’s that the believers have created this impression that sheriffs are beholden to no one.

This has become a widespread belief on both the right and the left. Both Democrat and Republican sheriffs will argue that they answer to no one (but the voters), and states tend to believe them. Lawmakers think that; the Department of Justice seems to think that. Sheriffs have somehow managed to persuade swaths of lawmakers that this is true, and it’s really hampered reform. It’s hard to change sheriffs or alter their departments because they’ve created this impression that they cannot be altered, their practices cannot be changed.

But it’s just not true. Even in states where sheriffs are embedded in the state constitution, which is about half of states (including Arizona), there are still lots of statutes that govern sheriffs.There just isn’t any legal justification to say that sheriffs are different from other elected officers.

So, there are mechanisms to hold sheriffs accountable, and one of the most interesting and promising, quite frankly, is just state lawmaking. They can simply make laws that alter the way sheriffs have to run their departments.

Q. Is there a state that has reduced the power of sheriffs?

A. Washington is one of the states that has attempted to create more robust state oversight. One of the things you can do there, if you have a complaint against your sheriff or the police, is go to a state oversight board who then has state investigators look into it. (Three years into the experiment, no investigations have been initiated by the oversight group.)

They’re also trying to pass a requirement for background checks for sheriff candidates. So basically, they’ve been trying to create state legislation that limits who can be sheriff and who they can hire.

In most places, to hold a sheriff accountable, you have to file a lawsuit, which of course, is very expensive. It puts the burden on the person who least has power. It requires that people come forward and make these allegations, which is very burdensome.

From my point of view, we need to reduce policing powers. One of the problems with the sheriff’s office as a whole is that it just has too many things. I don’t think county jails should exist, quite frankly, at all. But I think, in the meantime, that the county jail apparatus needs to be removed from the purview of the sheriff. Sheriffs have not shown themselves to be good stewards of jails, which are currently more unsafe than they ever have been.

Q: If the county sheriff didn’t run the jail, who would run it?

A. Seattle (King County) put its jail under an appointed executive. Similarly, other jails could use appointed officials, a person whose only job is to run the jail. They’re not elected. So the jail isn’t being used like a slush fund for contracts and favors. Of course, this isn’t perfect either, as the situation at Rikers Island in New York suggests.

Every sheriff will tell you their jail is the largest hospital in the county. They’ll say, oh, we run the largest mental health institution in the county. And they say it like it’s a job that they should be doing. But if it is, in fact, the largest mental health institution, then why on earth is a law enforcement officer running it?