An oval of sand and small rock slowly pours onto the polished cement floor. Mounted low on the four walls, speakers blurt out the grinding crunch of rock against rock — someone or something walking in a wash, or maybe merely the sonic hourglassing of time. In the exhibit by artist Karima Walker, “Graves for the Rain,” one thing is clear, there is not a drop of water.

The Tucson Museum of Contemporary Art, also called MOCA, has unveiled a poignant and timely new exhibit — made up of sculpture, performance and “quadraphonic sound” — by Walker, an artist and musician whose latest work bridges mediums to confront the ecological and cultural loss of the Santa Cruz River.

“Graves for the Rain,” Walker’s first solo museum exhibit, delves into the complex history of human interaction with the river and its current status as one of the most endangered waterways in the United States. The installation embodies Walker’s personal relationship with the river as well as a more collective meditation both on what Walker calls the river’s hydrological death and its potential for restoration.

A ring of river

“Graves for the Rain” is a shifting earthen sculpture, a ring composed of fluvial soil — basically dirt or sand that is pushed around by water — collected by Walker from the Santa Cruz’s west branch riverbed. Encircling the evolving sculpture is a sound piece, an ambient audio installation that loops recordings of the artist’s movements as she walks a circular path — in the “direction of the river flow,” says Walker — in the gallery space.

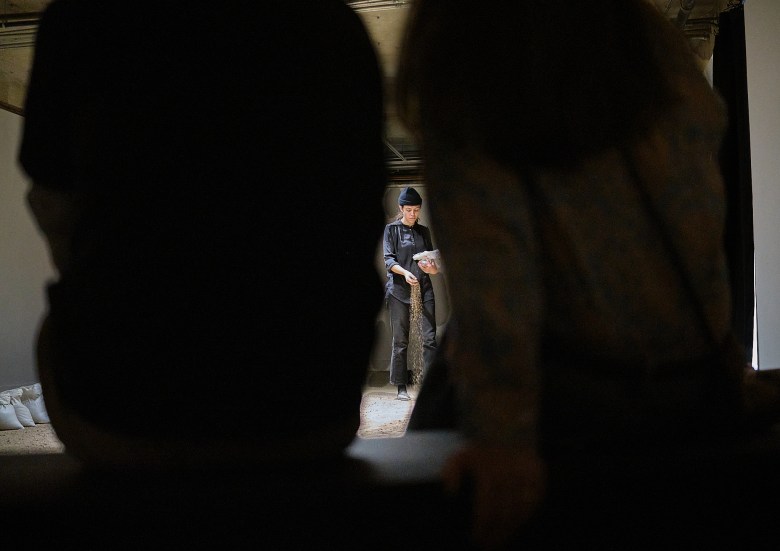

During the approximately two-hour long performances, Walker scatters what she calls river material onto the floor, layering the sculpture with traces of the river and her own footprints. The resulting continually changing installation is what Walker calls a “grief ritual,” or a performance that merges “burial and growth.”

Walker told Arizona Luminaria that the performances are “an invitation to consider individual and collective relations to the river.”

The history of the Santa Cruz

Flowing north from Sonora into Southern Arizona, the Santa Cruz River has served as a lifeline to Indigenous people for millennia. Over the past 150 years, however, the river’s ecosystem has been devastated by urban expansion, over-extraction, and the dumping of trash. By the early 20th century, the once-thriving waterway had largely dried up. That was when the river experienced “hydrological death.”

“We mined it for gravel and sand, we filled it with trash, and now we want to bring it back,” Walker said. But she also questioned what restoration’s aims were, cautioning against over-development along the banks.

“I want justice for this river. I want species to flourish, but I can’t take myself that seriously” to propose concrete policy aims, Walker said. “My job here is more like a skeptic or critic.”

In 2024, the Santa Cruz River was designated one of the most endangered rivers in the United States, an acknowledgment of its fragile state and uncertain future.

In a brochure accompanying the exhibit, Walker includes a further reading guide, with resources such as Watershed Management Group’s 50-year vision for the river and a poem about water and Indigenous relationships to rivers.

From environmental advocates to urban developers to poets, the fate of the Santa Cruz remains entangled in competing visions and priorities. That’s part of why Walker invites deep consideration of our relationship to the river.

How do we grieve for a river?

Walker said her art is inspired in part by her ecological work. She helped with remediation work in Southern Arizona with the Borderlands Restoration Network. She’s also volunteered with Watershed Management Group, which advocates for rainwater harvesting, native plant restoration, and aquifer recharge, to reverse the river’s decline.

During the performances, Walker said she feels a growing intimacy with the river. “I want to touch all of it,” she said of the river material she spreads. “I want proximity, knowledge.”

Natalie Diaz’s poem “The First Water Is the Body,” which was one of the inspirations for Walker’s exhibit, offers another lens through which to consider the human-river relationship. Diaz asserts the inseparability of water and the human body, writing, “The river is within us, as we are within the river.”

In a conversation with Arizona Luminaria, Walker wondered what it means to bear witness to a river’s death. What possibilities emerge when we reframe our relationship to water as one of reciprocity and care?

Walker’s exhibition at the MOCA will remain open through the coming months, inviting the community to engage with the Santa Cruz River’s past, present, and potential futures.

But Walker also warns that the oval shape of the growing sculpture is meant in part to “thwart this idea of linear progress.” She asks museum-goers to engage and meditate on the river and not be expected to provide easy answers about restoration.

Standing in the dimly-lit room a few days after a recent performance, Walker held a tall Nalgene water bottle in her hand. She crouched down to inspect a small dead insect that came along with the river material.

Leaning closer, she pointed out bits of trash, flecks of glass, and the occasional shimmer of mica.

As she stood, her shoe audibly crunched against a stray pebble.

“Can I really know this river?” she asked.