In the summertime, Keisha Kootswatewa and her family would travel the powwow circuit across the country and into Canada. Her daughters would dance with their dad. And Keisha would spend weeks beforehand sewing at their home on the Hopi Nation, handmaking their regalia.

“She beaded, she sewed, created things,” Yolanda Bydonie says, in awe of her cousin Keisha. “Not only was she busy with her kids, she was making these powwow outfits overnight.”

Keisha strived to give her three daughters a better childhood than the one she had growing up, Yolanda says. She graduated from Navajo Technical College in 2017 with an associate’s degree in public administration but instead of jumping into a career, she chose to dedicate herself to being a stay-at-home mom while her girls were young.

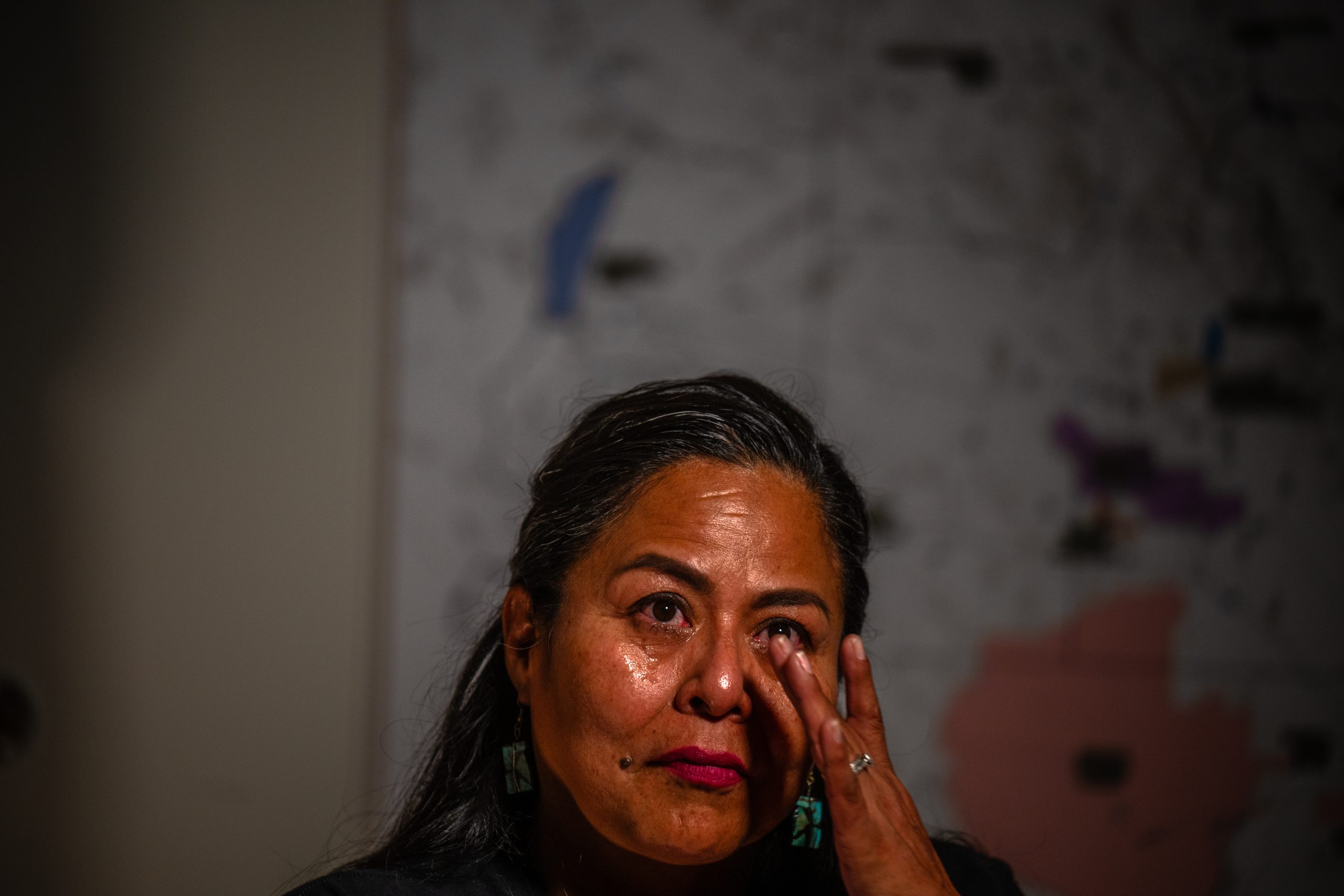

Yolanda is sitting in a car parked outside the Arizona State Capitol as she tells Keisha’s story to an Arizona Luminaria reporter. It’s a hot October day but she’s bracing to return to a chilly air-conditioned conference room, where leaders from across the country dedicated two days to issues surrounding Missing and Murdered Indigenous People.

Many in the room work as MMIP coordinators in their state and are gathering together for the first time in Arizona to discuss solutions in person.

There, Yolanda’s surrounded by government and tribal officials, forensic specialists and advocates hoping to strengthen efforts to resolve the injustice of Indigenous people who have been murdered or gone missing. Just before breaking for lunch, back-to-back speakers offered best practices for conducting searches.

Yolanda listened, but then she pulled out her phone to scroll through photos of her own search parties. She thought of Keisha. She’s always thinking of Keisha.

Brown hair and eyes. 5 feet, 6 inches tall with a medium build. And a few tattoos, including one that reads “Tewa” on her right forearm. Those are just a few of the words on a missing person flyer describing Keisha — a 32-year-old Hopi-Tewa woman who disappeared from the Navajo Nation almost three years ago.

But it’s clear when Yolanda speaks that Keisha is more than could ever fit onto a piece of paper. As in many Native families, she refers to Keisha as a sister. Though, she really thinks of her as a daughter since Keisha is the same age as her own daughter and spent many nights at their home.

Now whenever Yolanda talks about Keisha, it’s almost like they’re together again. Keisha is sarcastic and isn’t afraid to speak her mind. She is also kind-hearted and loving, especially when it comes to her family. They’d often get together for events and dinners, where Keisha took on the role of games coordinator – her favorite being kickball.

“Now, we do still do our family events, but we don’t have games,” Yolanda says quietly, as a look of realization washes over her face.

Missing Keisha has taken a toll on her family. Finding Keisha has turned Yolanda, a nurse by trade, into an investigator, advocate in training and whatever else it takes to see her loved one again.

‘It was radio silence’

Things took a turn in Keisha’s life when she and her daughters’ dad split up. Watching the life she built come apart was tough on Keisha and caused her to slip into depression, Yolanda says.

Soon, she began to stray from her family and fell in with the “wrong people,” she says.

It became common in the year leading up to Keisha’s disappearance for her family to not hear from her every day. Still, she’d regularly check in every couple of weeks and was often posting on social media.

Then one day in the spring of 2022, a friend of Keisha’s posted on their family’s Facebook group page asking if anyone had seen or heard from her.

“She always comes back around or posts on social media but she hadn’t been on for weeks,” Yolanda says. “It was radio silence.”

They were also contacted a short time later by the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs asking to speak to Keisha about an early morning shooting on March 26 in Teesto – a community on the Navajo Nation that borders the Hopi Nation. Yolanda says the agency wouldn’t share more details with them.

“She was with the wrong people, the wrong place, the wrong time,” she says.

That began Yolanda’s years-long investigation into Keisha’s disappearance. She says she went door-to-door asking questions about that morning and quickly learned from community members there’d been a house party that ended with two men shot and killed.

At least one person told the family that they saw Keisha taken alive at gunpoint, Yolanda says.

She and two other Navajo men — Damien Niedo and Micheaux-Michael Begaii — have not been seen or heard from since. Yolanda says the families have worked together to find their loved ones.

All three are logged on the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System, or NamUs, as missing from Teesto. However, Niedo and Begaii’s entries specifically note a “shooting incident” when they were last seen, while Keisha’s does not.

Becoming an investigator

By the time Yolanda pieced together Keisha’s last known whereabouts, she’d already been missing a few weeks. She then attempted to file a missing person report but was shuffled between the Navajo Nation Police Department and Hopi Law Enforcement Services before the latter “reluctantly” took the report, she says.

According to Yolanda, the BIA’s investigation was turned over at some point to the FBI due to the shooting allegations and Keisha being missing. She says the FBI has not been in contact with their family about its investigation.

“It really frustrated me, it really angered me,” Yolanda says. “It feels like you’re forgotten and wondering if they’re even doing anything about the case.”

Both Navajo and Hopi law enforcement agencies did not immediately respond to inquiries from Arizona Luminaria about Keisha’s case. An FBI spokesperson in an email to Luminaria said federal laws and policy prevented the agency from confirming or denying the existence of investigations.

“Regarding the family, while people are free to speak about their interactions with the FBI, we do not, as a matter of practice, discuss or describe any contact we have or allegedly have with individuals,” Kevin Smith, the bureau’s spokesperson, said.

That didn’t stop Yolanda. She continues to interview anyone who might have information about what happened to Keisha and follows up on possible sightings.

With help from Valaura Imus-Nahsonhoya, coordinator for the state’s Missing and Murdered Indigenous Peoples Task Force, Yolanda made the missing person flyer for Keisha and learned to organize searches. She’s led about a dozen so far, hoping but also dreading to find Keisha. Her GoFundMe campaign continues to raise money to support future searches.

Yolanda says she didn’t have a choice but to become her own investigator. She carries with her everywhere a binder full of notes, statements and any bit of information she’s heard about Keisha’s disappearance.

“This binder weighs on me,” Yolanda says, teary-eyed.

“I started to realize that this was consuming me and I was forgetting about my family,” she says. “Now I try to make some room to just put that aside even though I feel guilty knowing that she could still be out there.”

A shift into advocacy

Yolanda’s usually a private person – a trait she says is rooted in Hopi culture. And until Keisha’s disappearance, she wasn’t fully aware of the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women movement, even as it gained traction across the country in the past decade.

Now, she’s experiencing firsthand the barriers to justice that many Indigenous people face when a loved one goes missing or is murdered. “You don’t know until it happens to you,” she says.

Yolanda feels like she didn’t have a choice but to get out of her comfort zone to be a voice for Keisha. And the more she learns about other families who are experiencing the same trauma, the more she wants to help.

“We want to advocate for our Hopi people,” she says.

She has dedicated herself to learning more about advocacy, attending events and conferences like the National MMIP Coordinator Gathering in October. And she dreams of creating a nonprofit in Keisha’s name that currently only exists as a Facebook page to spread awareness.

Yolanda’s even encouraged her sister Skeena Cedarface to become more involved. Skeena recently became certified in mind and body therapies to help people from their community cope with the trauma that goes with having a missing or murdered loved one.

“There are cases, missing cases, murder cases, that we didn’t even know,” Skeena says. “Like families that are close to us in our community that we had no idea that they had a loved one missing.”

“We’re not a priority,” she says. “In the White man’s world, we have an Amber Alert, they find these kids, and where are we?”

Yolanda has shifted from her quiet, private life to sharing Keisha’s story with news organizations and at public events. In May, she emceed a Missing and Murdered Indigenous Peoples Awareness Day event outside the Arizona State Capitol.

“There’s one saying I heard and it has always stuck with me,” she told the audience. “When an Indigenous woman goes missing, she goes missing twice. First, her body vanishes. Then her story.”

“I will not let this happen to Keisha. I want the community to know who Keisha is and to remember she is valued,” she said. “I have become her strongest voice, because she’s silent out there.”

Stepping away from the mic, Yolanda is surrounded by Indigenous people who want their families whole again. She stands quiet behind the podium. Resting in the sunlight, until she needs to speak again for Keisha.